This is the seventh post of this section (Military Special Forces Throughout the World) and I’m so excited! First of all, I have never been in the military but I respect anyone who is active duty or is separated military. I have always been awed by regular military; you know those gun-hoe GI Joe types who rush into a room filled with hostiles and blow the ever living crap out of everything? Movies like Rambo (Sylvester Stallone), Commando (Arnold Schwarzenegger), Navy SEALS (Charlie Sheen), Delta Force (Chuck Norris) and Heatbreak Ridge (Clint Eastwood) come to mind.

It was only during recent years that I have actually started reading books about Special Forces and have personally met members of some of America’s elite Special Forces units that I have gained an absolute amazing respect for these men. I say “men” because, as of yet in America, women are not allowed to enter into a Special Forces unit. See my post: “Women in the Military: Should GI Jane Become a Reality?” to get a better picture of what I mean.

In the ensuing posts, I will give a profile of Special Forces groups throughout the world, describe their history and list a bunch of mind-blowing stuff they’ve done.

If you don’t know yet, Special Forces and Special Operations Forces are military components who are specially trained, drilled and educated to carry out un-traditional operations 1. Special Forces began in the early part of the 1900s, with a large expansion during WWII. This was a time when “every major army involved in the fighting” fashioned elite units who were loyal to special operations behind enemy lines.

Varying by country, Special Forces may execute some of these wicked, bad-to-the-bone ops: airborne missions, counter-insurgency, counter-terrorism, foreign interior resistance, clandestine operations, targeted warfare, hostage recovery, high-value targets/man-hunting, surveillance/reconnaissance missions, mobility ops and untraditional combat.

Be ready to be educated and blown away by what you’re about to read…

All of my previous posts about Special Forces have been about current special operations forces throughout the world. However, I became interested in a very unique group recently. Although they are no longer in existence, what they accomplished proves that they were very necessary for the period of time they operated.

There are certain levels of operations in the US military. Conventional forces such as Marine or Army infantry will carry out missions that are known to other military branches and, after they are completed, also to the general public. Special Forces usually operate beyond these missions in a unique, secretive realm. These are called clandestine, covert and black operations.

A clandestine operation is a mission that goes unnoticed by the public and the enemy. Covert operations go a step further and also conceal the “sponsor” of the operation. For example, the agents on a covert op don’t reveal who or what entity organized the mission or who they represent. Black operations (or simply black ops) are operations by a government, a government organization or a military group. This includes actions by contracted agencies 2. Black ops contain a large amount of disinformation or trickery in order to cover up the sponsor or to make it look like another party is responsible. These are also known as false flag operations 3,4. The group I’m writing about in this post, the SOG, operated under the Black Ops description.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG – aka MACSOG or just simply SOG) was a top secret, diversely functional US special operations team that practiced clandestine and some black ops untraditional combat missions before and during the Vietnam War 1. The missions they were sent on were so secretive that the US Government denied their existence. It wasn’t until their top secret operations were revealed that their true identity has been discovered and former SOG team members have come forward with their experiences.

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG – aka MACSOG or just simply SOG) was a top secret, diversely functional US special operations team that practiced clandestine and some black ops untraditional combat missions before and during the Vietnam War 1. The missions they were sent on were so secretive that the US Government denied their existence. It wasn’t until their top secret operations were revealed that their true identity has been discovered and former SOG team members have come forward with their experiences.

SOG worked in Vietnam and carried out their operations in the immense jungles of Southeast Asia. They had to overcome a crafty enemy of large numbers. Often, they had to call upon depths of fortitude seldom seen – even in war. If they made one miscalculation, one fleeting overlook, it meant certain death. The soldiers of SOG stared down fear and refused to turn away 1.

Even inside the military, the SOG was a closely guarded secret. They operated behind enemy lines with small six-man recon teams created to gather intelligence and impede with the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and their ability to engage in war against South Vietnam 1.

“You always heard rumors that they had this unit in Vietnam that was doing all this clandestine activity but no one was really sure what they were doing,”1

– Sgt. Edward A. Helfand – former SOG, US Army

“What did these guys do? Every now and then, you’d run into an old-timer with that thousand-yard stare who just got back. But no one was talking about it,”1

– Sgt. Brendon Lyons – former SOG, US Army

For these brave men, the costs were very high. Their casualty amounts were about 100%. Every single SOG member involved in recon was wounded at the very least. Those who were not were either killed or missing in action 1.

Against immense disadvantages, SOG found their way out, causing long-lasting damage to their enemy – and to themselves.

“It was almost like you were out of your body and you were watching. But that’s the attitude you have to take in order to survive.”1

– Sgt. Edward A. Helfand

Founded on January of 1964, SOG’s operations consisted of capturing enemy prisoners, rescuing downed pilots and conducting rescue operations to retrieve prisoners of war throughout Southeast Asia. They also conducted clandestine agent team activities and psychological warfare 1.

The unit participated in some of the most important offensives of the Vietnam War. They were formally disbanded and replaced by the Strategic Technical Directorate Assistance Team 158 (STDAT 158) on May 1, 1972 1.

History

For hundreds of years, Vietnam and China were at war. Then during the 1880s, the French claimed and colonized Vietnam. After the chaos of WWII, the French reestablished their presence in Southeast Asia and attempted to regain their colonial rule. It was harder than they thought. After the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the French retreated from Vietnam. This left a Communist government in the north that was supported by China and the Soviet Union. Ho Chi Minh reigned in the north and the fragments of Emperor Bao Dai’s dynasty ruled in the South. Into this unstable state entered the USA 1.

For hundreds of years, Vietnam and China were at war. Then during the 1880s, the French claimed and colonized Vietnam. After the chaos of WWII, the French reestablished their presence in Southeast Asia and attempted to regain their colonial rule. It was harder than they thought. After the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the French retreated from Vietnam. This left a Communist government in the north that was supported by China and the Soviet Union. Ho Chi Minh reigned in the north and the fragments of Emperor Bao Dai’s dynasty ruled in the South. Into this unstable state entered the USA 1.

America was then slowly pulled into the growing rivalry against the North and the South in Vietnam. Military leaders in the Pentagon became confident that the Communist North was fortifying a war machine that could begin an all-out clandestine war against the South. Ho Chi Minh’s goal was of a combined united Vietnam that was free of outside control. With the Soviet Union and China’s backing, he was ready to engage in a long war to achieve it 1.

After hearing of the increase in activity in the North, the CIA expanded the capacity and margins of their intel gathering activities in the south. In the aftermath of the CIA’s catastrophic Bay of Pigs raid in Cuba, an appraisal of CIA actions abroad determined that all extensive CIA missions were to be handed over to the military 1.

In January 24, 1964, MACV-SOG was conceived, taking over the duties, personnel and the mechanism of black-ops activities in relating to Vietnam 1.

SOG’s mission was: “To execute an intensified program of harassment, diversion, political pressure, capture of prisoners, physical destruction, acquisition of intelligence, generation of propaganda and diversion of resources, against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.” 5

The first leader of SOG was Colonel Clyde Russell and he had a difficult time creating a special operations group to complete this mission. At that time, no US Special Forces group existed that could carry out such an operation. The capacity of SOG’s mission enveloped so many aspects that a single US special operations team couldn’t accomplish 6. Individual Special Forces teams couldn’t include agent, naval and psychological characteristics in one operation.

After a slow and unsure beginning, SOG began some of its first operations that continued with CIA agent insertion. South Vietnamese volunteers dropped into North Vietnam but most of them were taken prisoner. They also tried clandestine maritime missions off the North Vietnamese coast using specially built patrol boats but these missions were also relatively unsuccessful.

It was then decided that SOG would be formed by doing something never before accomplished in the US military – Russell combined the sharpest, most elite members of the US Special Forces to form the first SOG teams. The newly formed Navy SEALs were experts in maritime operations. The Army’s Green Berets were practiced in winning the hearts and minds of local villagers and forming indigenous militias. Marine Force Recon were specialists in long range reconnaissance and surveillance. The Air Force’s Combat Controlers were highly skilled in combat communication and calling in bombing runs. The newly founded SOG would include volunteers from all these Special Forces groups to form their own unique cell of elite, specialized operators that could fulfill the mission. It was taking the best of the best and inserting them into some of the harshest environments in Southeast Asia to complete black-operations specifically crafted for their unique skills and abilities.

It was then decided that SOG would be formed by doing something never before accomplished in the US military – Russell combined the sharpest, most elite members of the US Special Forces to form the first SOG teams. The newly formed Navy SEALs were experts in maritime operations. The Army’s Green Berets were practiced in winning the hearts and minds of local villagers and forming indigenous militias. Marine Force Recon were specialists in long range reconnaissance and surveillance. The Air Force’s Combat Controlers were highly skilled in combat communication and calling in bombing runs. The newly founded SOG would include volunteers from all these Special Forces groups to form their own unique cell of elite, specialized operators that could fulfill the mission. It was taking the best of the best and inserting them into some of the harshest environments in Southeast Asia to complete black-operations specifically crafted for their unique skills and abilities.

The idea of SOG’s approach to war had its origins in the American Revolution, when the desire for unconventional tactics led to success on the battlefield. The paramilitary strategies utilized by colonial militias picked off the British in their conveniently bright red coats as they continued across the American backwoods. In WWII, the Office of Strategic Services (the OSS – predecessor to the CIA) sent agents behind enemy lines to work with local groups in acts of intel gathering and sabotage. The SOG would continue with this same mission and carry on the tradition of using the talents of various Special Forces teams to integrate the SOG mission into the theater of the Vietnam War 1.

Hearts and Minds – Recruiting Local Militias

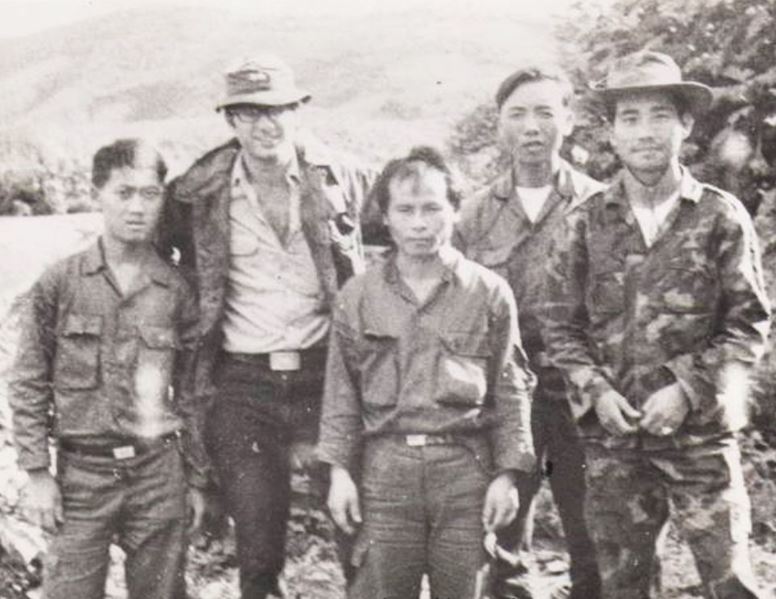

SOG formed recon teams combining two or three American troops and two or three indigenous troops – Vietnamese, Hmong tribesmen or Montagnard (the French word meaning “mountain people”). Recruiting the indigenous fighters led to some interesting encounters 1.

Once the teams were put together, special training began. It was the acute skills of the SOG members who were drawn from the military’s elite that meant the difference between life and death for the militias they trained – despite being vastly outnumbered 1.

“We didn’t want to make contact with the enemy, but it doesn’t work out like that most of the time. The whole idea was to gather intelligence and you would report all this information back to HQ and they would map it out,”1

– Sgt. Edward A. Helfand

Ready for War

From the beginning of their time in Vietnam, the members of SOG knew the rumors only hinted at the way their new world was a part of a separate top-secret reality 1.

“I will always remember the first SOG brief I got. I finally found out what we were doing, Colonel Jack Warren was wearing a green beret, a black wind-breaker, shower shoes and smoking with a cigarette holder. He flamboyantly threw back this curtain and here’s this map of Southeast Asia. I’m look at one side, which is Vietnam, but all these boxes that are on the west side of the map which is Laos. Then Col. Warren said, ‘Gentlemen, welcome to the covert world,’”1

– Major John Plaster – former SOG, US Army

With the arrival of America’s first combat troops in South Vietnam in 1965, the state of Southeast Asia shifted into an official armed conflict 1.

“We had three major command control detachments. From these bases, we would launch our teams into Cambodia and Laos,”1

– Colonel S. E. Cavanaugh, US Army (retired)

SOG Day-to-Day Operations

The soldiers of SOG brought absolutely nothing with them and wore no clothing that would reveal their identity as Americans when they conducted recon clandestine ops. Of the roughly 2,000 SOG members, only 200 were assigned to recon 1.

Some SOG operators would wear black hats with a red communist star. If anybody saw them, they would assume they were Russian advisers. Other SOG members would wear North Vietnamese Army uniforms as to confuse the enemy into thinking they were friendlies. Any time SOG teams deployed on clandestine ops, they knew that if they were caught, they had to deny any ties to the US. They were totally on their own and risked everything until they safely returned to headquarters 1.

Teams carried enough weapons, food and water to get them through a 5-day recon mission. The favorite SOG firearm was the automatic CAR-15, a modified M-16 with a stock that expanded or contracted 1.

“We would always carry a basic load of 550-600 rounds for the carpet team, about 10 hand grenades and a dozen or more rounds for the M-79 grenade launcher. For the gear, we always carried between 80-90 pounds,”1

– Sgt. John S. Meyer – former SOG, US Army

During day-time missions, SOG teams received the support of a forward air controller or a FAC. FACs flew in a small single engine prop plane and maintained radio contact with the teams 1.

During day-time missions, SOG teams received the support of a forward air controller or a FAC. FACs flew in a small single engine prop plane and maintained radio contact with the teams 1.

“You always wanted the FAC to know where you were. A good radio operator would let the FAC know they were in a certain location. The reason behind that was if someone shoots at you or you need an immediate exfil, he doesn’t need to search around to find where you are,”1

– Sgt. Edward A. Helfand

To fulfill their mission, SOG recon teams, like they were always known for, showed up unconventionally and passed through the jungle undetected 1.

“Ideally, you’re going to land. Three guys get off, another helicopter would come in and another three guys get off and we’d go on from there. Occasionally, because of the terrain, we would rappel in or go down a ladder,” 1

– Sgt. 1st Class Cliff Newman – former SOG, US Army

“I remember the sound of the helicopters. You get ready to go into the landing zone and it was very very noisy. You’d get on the ground, the helicopter would take off and all of a sudden, there was silence. All you’d hear is the jungle sounds of bugs,”1

– Sgt. Edward A. Helfand

“You’d never talk at all when you’re out in the bush. There were do’s and do not’s. One of the big do not’s was verbally communicating when you’re out in the field. Listen for sounds – that was another key thing I remember was you always listened. You wanted to hear the natural sounds – the birds, the monkeys and insects. Normally, if you didn’t hear that, there was something that might be going on. There may be an ambush being set up. People might be in place, which frightens the animals who may be super quite. So if you heard quiet, normally something was amiss,”1

– Sgt. William J. Deacy – former SOG, US Army

“When you do this type of operation, stealth is the most important thing. So you walk very slowly and that’s how you would see a lot of things because the enemy couldn’t hear you. So you’d walk around, stop and use hand signals,”1

– Sgt. Edward A. Helfand

Sometimes, no matter how silent, no matter how well the teams navigated off the trails, there were unavoidably times when they came in contact with the enemy. The NVA used their own spotters and trackers who searched for SOG recon teams. From the instant they landed, SOG operators were key enemy targets 1.

Notable Operations

Psychological Warfare

Aside from conducting direct action against the enemy, the SOG’s original missions also entailed psychological warfare against North Vietnam. The SOG’s Navy component acquired fishermen from North Vietnam and confined them to a South Vietnamese island, although they were told that they were still in their homeland 15.

Aside from conducting direct action against the enemy, the SOG’s original missions also entailed psychological warfare against North Vietnam. The SOG’s Navy component acquired fishermen from North Vietnam and confined them to a South Vietnamese island, although they were told that they were still in their homeland 15.

The inhabitants on this island acted like members of a sectarian northern communist group called the Sacred Sword of the Patriot League (SSPL), which disputed the overthrow of the Hanoi regime by leaders who supported Communist China. The captured fishermen were well taken care of but they were also carefully questioned and indoctrinated in the ideation of the SSPL. After two weeks, the fishermen were returned to their actual homeland in northern Vietnam 6.

This myth was backed up by the radio publications of SOG’s “Voice of the SSPL“, flyer drops and gift kits including radios that broadcasted from the unit’s transmitters. SOG also transmitted “Radio Red Flag” propaganda that was allegedly run by a group of nonconforming communist military officers from the NVA. Both radio broadcasts were uniformly resolute in their disapproval of the PRC (People’s Republic of China), the South and North Vietnamese establishments and the US. They demanded a return to traditional Vietnamese principles. Straight forward news, without indoctrination was transmitted from South Vietnam by the “Voice of Freedom”, another station that was ran by SOG 6.

This myth was backed up by the radio publications of SOG’s “Voice of the SSPL“, flyer drops and gift kits including radios that broadcasted from the unit’s transmitters. SOG also transmitted “Radio Red Flag” propaganda that was allegedly run by a group of nonconforming communist military officers from the NVA. Both radio broadcasts were uniformly resolute in their disapproval of the PRC (People’s Republic of China), the South and North Vietnamese establishments and the US. They demanded a return to traditional Vietnamese principles. Straight forward news, without indoctrination was transmitted from South Vietnam by the “Voice of Freedom”, another station that was ran by SOG 6.

These channel mediums and publicity attempts were run by SOG’s air arm, the First Flight Detachment. The team was made up of four C-123 aircraft that were considerably altered and piloted by Chinese aircrews who were hired by SOG. The airplanes also conducted agent drops and supply operations, pamphlet and gift kit drops and implemented periodic planning operations for SOG 6.

Echo 4

In October 1968, John Meyers’ team was assigned target Echo 4.

“We moved for a whole day. However, the trackers began to close in on us,” Meyers

remembered, “They found our trail somewhere. By night, they were within 25-30 feet of us. So first light, we move out and at about 1:30 in the afternoon (we had been moving all day), we got to the top of a little hill and set up there. I called the tactical and said, ‘Try to get somebody in the air because we’re going to have contact here,’

“They finally hit us at about 2:00. They came after us wave after wave and we blew them back down the hill over and over. At one point, they began stacking their bodies up because we had killed so many of them. But when they first opened up, when that first jolt hit, it was almost like an apocalyptic death roar.” 1

Finally, the air cover arrived including helicopter gunships and A-1E Skyraiders carrying napalm. The mission to target Echo 4 was over. The goal then was to hold the enemy back and bring a helicopter in to carry the SOG team back to base and to safety. The transport helicopter couldn’t get in right on top of the SOG team. Instead, they had to fight their way through 25 foot high elephant grass to reach the chopper, their ride home.

“There stood the helicopter, the gunships are coming around doing gun runs to suppress any fire. We finally get to the helicopter and literally throw everybody in there. It’s just hovering there. I looked up and Captain Tin was just sitting there as cool as a Rocky Mountain breeze, ‘Okay guys, any time you’re ready to go home, I’m ready,’” recalled Sgt. Meyers 1

And like so many things surrounding the Vietnam War, the contrast at the edge of life and death were always extreme.

“One minute, you’re feeling trauma to the max. They’re trying to get us the gunships and all this turmoil. We get back to base and all the guys are there like, ‘Hey, you guys got back great!’ and you’re going, ‘Wait a minute! We just barely got out of there!’ Then one of my buddies who was there asked how it had gone and I said ‘really bad’. He wanted to know if we had killed anybody,”

Sgt. Meyer closed by saying, “I had to think about it that that day was the first time I had killed somebody. But in the heat of it, you don’t think about it. And then you talk about it but you just can’t let it bother you. If you didn’t get him, he would have gotten you and you wouldn’t have gone home,” 1

Prisoner Snatch

As the Veitnam War continued and escalated, the pressing need for more specific information about enemy troop and supply movements down the Ho Chi Minh Trail grew more urgent.

“The North Vietnamese were really good at camouflaging their vehicles during the day,

moving them at night and then they’d bring the supplies down into South Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia by vehicle. We were interested in trying to determine where these things came from, what was being carried in them and where they were unloading them and any routes they were using to get into South Vietnam,” 1

– Col. Steve E. Cavanaugh

Sending teams in to watch the trail didn’t accomplish the task of gathering all the vital intel that was needed. Only one method could achieve that desired goal, one of the riskiest jobs ever handed out to any SOG recon team – the prisoner snatch. This entailed capturing an NVA soldier from Laos or Cambodia and returning with him to a SOG base in South Vietnam for interrogation.

“In March 1970, there had been a series of convoys riding on highway 110 in southern Laos right up to the border of South Vietnam. That’s where they would disappear. Supplies were being stockpiled for some major action.” 1

– Maj. John Plaster

SOG one-zero, John Plaster, was given the task of snatching a prisoner. He devised a plan and drilled his team nonstop for two weeks to achieve optimum performance levels.

SOG one-zero, John Plaster, was given the task of snatching a prisoner. He devised a plan and drilled his team nonstop for two weeks to achieve optimum performance levels.

The most important person to grab was the head driver in a supply convoy. This man would know exactly where their supplies came from and where their destination was. If this was true and the intel could be utilized, B-52s would be deployed to drop bombs on those locations.

Finally, the time came to put the risky plan into action. Remotely triggered claymore mines would be used to immobilize the lead truck.

“I still remember that first night as we were laying on a hillside about 2 kilometers from the highway. We could hear the trucks rolling down the road. It was both exciting and fearful. We knew they were there. The next night, we would be down on that highway. We reached it about noon,” 1

– Maj. John Plaster

Everything was in place. There was only one thing left to do – probably the hardest thing of all – and that was to wait. Just at the point of darkness, Plaster deployed flank security teams.

Two hours later, the first truck came into view. After the claymores exploded and immobilized the convoy, the SOG team sprang into action and jumped onto the road. One operator grabbed the driver in the lead truck while another ran around to see if there was a passenger. After no passenger was found, another SOG member discovered a stockpile of supplies in the truck bed. There was no resistance at all and not only did they stop more supplies from reaching their destination but the SOG team apprehended the driver who would hold vital information.

With the driver in custody, there had still been no contact with the enemy until team member Richard Woody sounded the signal to withdraw.

All of a sudden, he was hit twice in the arms with bullets and was badly injured. Plaster bundled him up to stop the bleeding and handed him off to the rest of the team who were headed for the rendezvous sight back in the jungle.

Their intel had predicted an NVA battalion basecamp that was about ½ mile away and held about 500 NVA troops. The team knew they could not stay there for very long.

Plaster stayed behind to cover his team’s withdraw and blew up the truck. The truck then caught fire and provided a beacon for fighter jets who were able to bomb up and down the road all night long. This kept the enemy restrained along the road. They were so pre-occupied by the bombing that they never caught up with the SOG team.

Plaster and his SOG team trudged through the jungle almost all night until they arrived at the LZ about an hour before dawn. Back at HQ, there was no marching band, no photographer and no medals ready to be awarded. SOG members were never informed of the product of their life and death ventures. However, their accomplishments were well known throughout Special Forces circles. The first prisoner snatch was a very courageous op and every single team member contributed.

Bat-21 Rescue

On April 2, 1972, during the NVA Easter Offensive, the largest combined arms operation in the Vietnam War, a US Air Force EB-66 electronic warfare plane (call sign “Bat-21 Bravo”) was shot down by a SAM missile. Of the six crew members, the navigator, 53-year-old Lt. Col. Iceal “Gene” Hambleton (a veteran of WWII and the Korean War), was the only one to make it to the ground alive. As he surveyed his surroundings, he realized that the was behind enemy lines and in the vicinity of more than 30,000 NVA troops! He possessed a wealth of knowledge on top secret information and would have been interrogated and tortured if he was captured. Needless to say, it was imperative that he was rescued and didn’t fall into enemy hands. However, time was against a rescue attempt, as the odds of recovering downed airmen dropped below twenty percent if the aircrew member was on the ground after four hours 23.

Several rescue attempts were made but they failed. This resulted in the loss of five more aircraft and the death of 11 or more airmen, two were captured and three were evading the enemy – 1st Lt. Mark Clark, 1st Lt. Bruce Walker and Lt. Col. Gene Hambleton. Because of Hambleton’s high value, it was decided that the downed airmen were going to be rescued regardless. There was only one qualified team to go in – the SOG.

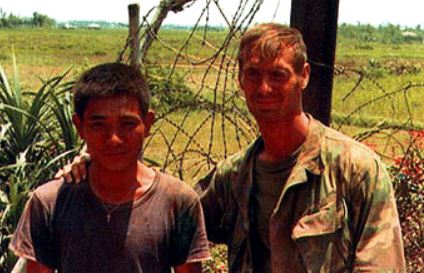

SOG Lt. Col. Andy Anderson knew the perfect person for the job. SOG Navy SEAL Lt. Tom Norris (one of the last remaining SEALs in Vietnam), was tasked with leading a ground search and rescue operation to recover Hambleton, Clark and Walker. He recruited five Vietnamese Sea Commando team frogmen from the Naval Advisory Detachment.

The rescuer’s original plan was to swim upriver and meet Clark but Norris tested the current and decided it was too strong. They would have to insert along the riverbank, a much more hazardous route 7. Lt. Col. Anderson, Norris and five Vietnamese commandos set up an over-watch position near the Mieu Giang River, which ran near the positions of two of the downed airmen 8. Walker was positioned further inland. Anderson ordered Norris to take his team no more than 1 kilometer (0.62 mi) down-river and wait for the survivors to come to them but after departing, Norris ignored the order and turned off his radio. Traveling twice that distance upriver, he avoided frequent NVA patrols, trucks and columns of tanks 9.

Clark was the first pilot who would be rescued. Following instructions he received over the radio, he floated down the cold river 10. After a close encounter with an NVA patrol, Norris found Clark hiding behind a sampan fishing boat on the riverbank. Norris then safely delivered Clark to the forward operating base 9.

On April 11, 9 days after he was shot down, Hambleton was too weak to move any farther. He was holed up in some bushes in a dry rice field. Norris was well aware of the overwhelming NVA presence but decided to proceed upriver again. He could only follow parts of Hambleton’s weak radio signal but knew he would have to go to him 11. After two Vietnamese commandos were wounded in a mortar attack, Norris was left with only three who barely spoke English. After searching for Hambleton on the night of April 12, two of the commandos declined to continue any further. They didn’t want to follow an American just to rescue an American 12.

On April 11, 9 days after he was shot down, Hambleton was too weak to move any farther. He was holed up in some bushes in a dry rice field. Norris was well aware of the overwhelming NVA presence but decided to proceed upriver again. He could only follow parts of Hambleton’s weak radio signal but knew he would have to go to him 11. After two Vietnamese commandos were wounded in a mortar attack, Norris was left with only three who barely spoke English. After searching for Hambleton on the night of April 12, two of the commandos declined to continue any further. They didn’t want to follow an American just to rescue an American 12.

Norris was prepared to do the mission alone when one of the last remaining South Vietnamese commandos, Petty Officer 3rd Class Nguyen Van Kiet 9 volunteered to go with him 13. The duo worked their way slowly upriver until they came upon an abandoned, destroyed village 14 where they disguised themselves as fishermen and commandeered a sampan. They rowed quietly up river but even in the pitch dark and dense fog they could see large numbers of NVA soldiers and tanks on the shore. They finally found Hambleton sitting in a clump of bushes. He was alive but was delirious and extremely weakened, having lost 45 pounds since he was shot down 11. Dawn was approaching and although Norris thought it was best to wait until dusk to return downriver, Hambleton needed to be evacuated immediately. Despite the risk of a daylight evacuation, they hid Hambleton in the bottom of the sampan, covered him with banana leaves and started their trip downriver 9.

As they approached a bend in the river, NVA troops spotted them and opened fire. Norris and Nguyen couldn’t afford to return fire but instead paddled with all they had to try and escape the intense fire. They soon found a current in the middle of the river and headed downstream toward another turn. As the river straightened out, they were faced with an onslaught of heavy NVA machine guns. The men quickly ditched their boat on  the opposite bank and took cover. They were able to call in the positions on the NVA troops and several Navy planes dove down and took out the NVA soldiers. Returning to the river, the three men were soon able to receive support from South Vietnamese forces. Landing on the river bank, they were met by some ARVN soldiers. Hambleton was unable to walk and they carried him back to their bunker. Hambleton, Norris and Nguyen were then transported back to Headquarters in Dong Ha 9.

the opposite bank and took cover. They were able to call in the positions on the NVA troops and several Navy planes dove down and took out the NVA soldiers. Returning to the river, the three men were soon able to receive support from South Vietnamese forces. Landing on the river bank, they were met by some ARVN soldiers. Hambleton was unable to walk and they carried him back to their bunker. Hambleton, Norris and Nguyen were then transported back to Headquarters in Dong Ha 9.

Later, a news reporter asked Norris, “It must have been tough out there. I bet you wouldn’t do that again.” Norris replied, “An American was down in enemy territory. Of course I’d do it again.” 9

Regardless of the heroic rescue of Clark and Hambleton, 1st Lt. Bruce Walker was still over 1 kilometer behind enemy lines. He managed to evade capture for almost 11 days when on the night of April 18, he ran into a local villager who alerted the North Vietnamese 10. An FAC plane flying overhead witnessed 20 NVA soldiers surrounding Walker and shortly afterwards, he fell to the ground. His body was never recovered.

Hambleton received the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, the Meritorious Service Medal and a Purple Heart for his actions during the mission. Petty Officer 3rd Class Nguyen Van Kiet was the only South Vietnamese soldier who was honored with the second highest medal in the US military – the Navy Cross. For his heroic actions in rescuing Hambleton behind enemy lines, Lt. Thomas R. Norris received the Medal of Honor.

In 1973, the captured downed pilots were released from an NVA POW camp. Overall, there were 234 medals handed out to all those who participated in the Bat-21 rescue recovery. In 1975, the rescue mission was declassified.

The First HALO Jump

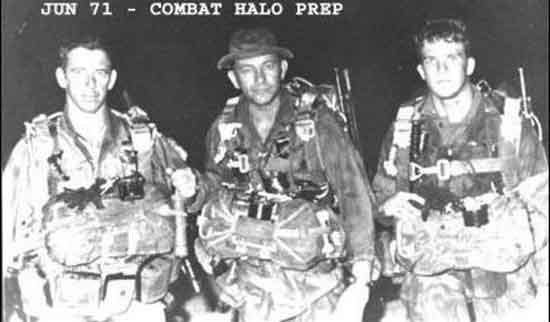

The more the war drew on, the more refined techniques were cultivated on both sides. Due to the Ho Chi Minh trail’s location, the thorough understanding of the landscape obtained by the NVA, most of SOG’s landing zones were known and were regularly observed by the enemy. It was time to try something different. SOG Staff Sergeant Cliff Newman was already a seasoned sky diver prior to joining the Special Forces. He was the logical choice to head up a strategic experimental operation. The new approach was nicknamed “HALO” for “high altitude, low opening”. This entailed parachuting above 18,000 feet, free falling and opening the parachute at just 1,500 feet above the ground 1, 20.

The C-130 ramp slowly opened up. The deafening combined sound of wind and engines came to the six men of SOG’s recon team “Florida” as they waddled in their gear to the opening. They had been through one month of training and everything lead up to this very moment. The team was made up of Staff Sergeant Cliff Newman (the leader), Sergeant First Class Sammy Hernandez, Sergeant First Class Melvin Hill, two Montagnards and a South Vietnamese Army officer. As they took it all in, they were met with a dark expanse of Laotian sky and realized it was raining heavily. It didn’t matter however because they couldn’t turn back 1, 20.

The C-130 ramp slowly opened up. The deafening combined sound of wind and engines came to the six men of SOG’s recon team “Florida” as they waddled in their gear to the opening. They had been through one month of training and everything lead up to this very moment. The team was made up of Staff Sergeant Cliff Newman (the leader), Sergeant First Class Sammy Hernandez, Sergeant First Class Melvin Hill, two Montagnards and a South Vietnamese Army officer. As they took it all in, they were met with a dark expanse of Laotian sky and realized it was raining heavily. It didn’t matter however because they couldn’t turn back 1, 20.

When the jumpmaster gave the go command, the team stepped off into the void and plummeted through the stinging rain. This wasn’t just another SOG mission. These six men were making the first ever combat HALO jump. They were stepping off that ramp into military history 1, 20.

“When you fall through rain, it’s like being poked with icicles or icepicks. It was a weird feeling. There I was falling in a rain storm looking at my altimeter wondering where I am. When I opened, I was just coming out of the clouds and I saw the terrain features. It was very dark – about 2:00 in the morning. I landed in the drizzling rain all by myself. I figured that was the stupidest thing I’ve ever done in my entire life!” 1

– Sgt. Cliff Newman

Newman and the other SOG members made it to the ground in one piece. After reassembling together, they remained in the area for five days totally undetected. The essential objective of inserting a SOG team had been done. The mission was considered a win 1.

Today, HALO jumps have developed into a science (and sometimes an art-form) with the expertise obtained during the Vietnam War granting covert operations forces to be inserted essentially unchallenged at any location and at any time. Combat HALO jumps are one of the valued practices that has made SOG operators legendary. The HALO jumpers who returned with SOG became the foundations for what became Army and Navy special ops. These men were SOG veterans. The lessons and methods of HALO jumping expanded throughout international special forces and is practiced all over the world 1.

Heroes

Staff Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez (see my blog post about Benavidez)

Staff Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez (see my blog post about Benavidez)

On the morning of May 2, 1968, a 12-man SOG recon team was dropped by helicopters in a thick jungle west of Loc Ninh, Vietnam. Their mission was to obtain info about enemy troop movements. The area they were in was inhabited and frequently watched by the NVA. After they were on the ground for only a short time, the SOG unit came under heavy enemy fire and called in for an emergency evac 16, 17.

Three attempts were made but no helicopter was able to land because of the heavy enemy small arms fire and anti-aircraft attacks. Benavidez was at the FOB (Forward Operating Base) observing the mission over the radio when several helicopters arrived to unload the wounded and regroup. Benavidez then entered one of the hueys voluntarily to help out in the next rescue effort 16, 17.

When the huey arrived at the scene, Benavidez instructed the pilot to land in a clearing  that was close by instead of near the SOG team that was pinned down. Once near the ground, Sgt. Benavidez, armed only with a knife and a medical bag, jumped from the still hovering helicopter and ran about 80 yards under heavy enemy fire to the immobilized SOG unit. Once with the SOG team, Benavidez rallied the few able-bodied men remaining and directed their fire towards the advancing NVA. He then called in artillery to the enemy positions. He also oversaw the landing of additional aircraft to load the wounded and dead. He was hit multiple times by enemy small-arms fire and received shrapnel wounds from grenades. However, he continued to fight. At one point, he faced an NVA soldier who stabbed him with a bayonet. Benavidez simply pulled it out and stabbed him to death 16, 17!

that was close by instead of near the SOG team that was pinned down. Once near the ground, Sgt. Benavidez, armed only with a knife and a medical bag, jumped from the still hovering helicopter and ran about 80 yards under heavy enemy fire to the immobilized SOG unit. Once with the SOG team, Benavidez rallied the few able-bodied men remaining and directed their fire towards the advancing NVA. He then called in artillery to the enemy positions. He also oversaw the landing of additional aircraft to load the wounded and dead. He was hit multiple times by enemy small-arms fire and received shrapnel wounds from grenades. However, he continued to fight. At one point, he faced an NVA soldier who stabbed him with a bayonet. Benavidez simply pulled it out and stabbed him to death 16, 17!

Not only did Benavidez save the lives of 8 SOG team members but he also secured or destroyed vital top-secret documents that were with the team leader. During another time, an incoming Huey crashed near his position. Although mortally wounded himself, Benavidez extracted the wounded pilot and other flight crew to another awaiting helicopter 16, 17.

After six hours of intense enemy fire, suffering 7 gunshot wounds, 28 shrapnel holes and 2 bayonet injuries, Benavidez allowed himself to be loaded up in a med-evac helicopter. He was withdrawn to the FOB, analyzed by a doctor and determined to be dead. As he was being zipped up in a body-bag, Benavidez was able to spit at the doctor, alerting him that he was still alive 16, 17!

He recovered from his wounds and returned to the US. At first, Benavidez was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. It wasn’t until 1981 that President Reagan presented him with the Medal of Honor.

Staff Sergeant Franklin D. Miller

On January 5, 1970, SSgt. Miller was commanding an American-Montangard recon patrol that was deep behind enemy lines in Laos. After one of the Montangards triggered a booby trap, five of the team members were severely wounded, including Miller. Knowing the sound of the explosion would alert the enemy, Miller lead the team across a stream at the bottom of a hill 18.

On January 5, 1970, SSgt. Miller was commanding an American-Montangard recon patrol that was deep behind enemy lines in Laos. After one of the Montangards triggered a booby trap, five of the team members were severely wounded, including Miller. Knowing the sound of the explosion would alert the enemy, Miller lead the team across a stream at the bottom of a hill 18.

With the rest of his men securely hidden, SSgt. Miller met two separate NVA attacks by himself. Miller rejoined his men, contacted a Forward Air Controller and lead his team toward an exfil point. When the rescue helicopter arrived, Miller courageously held off an additional enemy attack. However, the med-evac helicopter had to leave due to the immense enemy fire. SSgt. Miller then lead his team to another sight and held off two additional enemy attacks until a relief force reached them. In 1971, Miller was presented with the Medal of Honor by President Richard Nixon 18.

Specialist Five John J. Kedenburg

Specialist Five John J. Kedenburg

Kedenburg served as an advisor to a long-range recon team of South Vietnamese guerillas. Their mission was to operate deep within enemy territory and locate enemy troop movements. On June 14, 1968 before arriving at their target, the team was ambushed and surrounded by a large number of NVA. Kedenburg took instant control of the situation. After a vicious firefight, the team was able to escape certain death and maneuvered into the jungle away from the NVA force 19.

They continued to move through the dense jungle as Kedenburg called in an extract and air support helicopters. Kedenburg held up the rear of the retreat and fought off any enemy who followed. As they arrived at the LZ, all heads were accounted for except for one. Kedenburg distributed his team into a fortified defense against the NVA forces who greatly outnumbered them. Once air support gunships arrived, he directed their fire against the enemy, holding off their attacks so evac helicopters could drop slings so the team to be hoisted up 19.

With half the team safe in their harnesses, Kedenburg and 3 team members remained. As they were fitting into the slings, the missing South Vietnamese team member rushed out of the jungle and ran in to the landing zone. With total disregard for his own life, Kedenburg gave up his place and offered it to the South Vietnamese soldier. He then commanded the helicopter to leave the area. As the rescue helicopters departed, he was seen engaging the superior enemy who were overrunning the landing zone. He took out 6 enemy soldiers before he was overpowered and killed. For his gallant actions, unwavering courage and self-sacrifice, John J. Kedenburg posthumously received the Medal of Honor 19.

Withdrawal

In 1971, the American withdrawal from South Vietnam began to directly affect SOG. Furthermore, US military was not allowed to operate in Laos or Cambodia. SOG’s mission was then redirected to in-country operations. It was also continuously assigned with providing teams ready to operate in North Vietnam if needed.

In late March of 1971, the 5th Special Forces Group (the Green Berets, which made up most of SOG operators) was redeployed back to the US. Command and Control aspects were re-designated as Task Force Advisory Elements. They were initially made up of 244 US and 780 indigenous forces but were reduced by the withdrawal of the exploitation troops. For the SOG, the responsibility of Vietnam was finally handed over to the indigenous population.

On May 1, 1972, they were decreased in substance and re-designated as the Strategic Technical Directorate Assistance Team 158 (STDAT-158) 5. The Ground Studies Group was dissolved and reinstated as the Liaison Service Advisory Detachments. SOG’s air units withdrew for redeployment, the JPRC (Joint Personnel Recovery Center) was renamed the Joint Casualty Resolution Center and psychological operations were passed over to other responsible organizations 21.

Eventually, the Strategic Technical Directorate Assistance Team 158 took complete control over all SOG operations until it was also disbanded on March 12, 1973 22. In January of 1973, President Richard Nixon ordered a conclusion to all US combat missions in South Vietnam. A peace treaty was agreed upon by the belligerent powers in Paris later that month. On February 29, 1973, MACV was dissolved and all remaining US forces began leaving South Vietnam. On August 14, the US Air Force discontinued bombing of Cambodia, ceasing all US military operations in Southeast Asia.

Conclusion

During the aftermath of the Vietnam War, SOG numbers added up. Out of the 2,000 special forces personnel in SOG, about 200 were assigned to recon. At any given time, about 60 operated across the border into Laos and Cambodia. Of those 60 SOG operators, their operations in Laos and Cambodia were sufficient enough to hinder 40-60,000 North Vietnamese from entering South Vietnam. This was an overwhelming impact. Maybe even the greatest economy of force operation in the history of the US military. Because of the perils confronted by SOG operators, America’s military troops carry on their advantage in today’s complex environment. The SOG teams were ready to shoulder the challenging missions they were called to do without asking for any recognition. Now that one can view this hardline team of special operators in hindsight and that the veil of secrecy has been lifted, you can now understand the amazing efforts, impact and risks that were accomplished by the few brave soldiers of the SOG 1.

During the aftermath of the Vietnam War, SOG numbers added up. Out of the 2,000 special forces personnel in SOG, about 200 were assigned to recon. At any given time, about 60 operated across the border into Laos and Cambodia. Of those 60 SOG operators, their operations in Laos and Cambodia were sufficient enough to hinder 40-60,000 North Vietnamese from entering South Vietnam. This was an overwhelming impact. Maybe even the greatest economy of force operation in the history of the US military. Because of the perils confronted by SOG operators, America’s military troops carry on their advantage in today’s complex environment. The SOG teams were ready to shoulder the challenging missions they were called to do without asking for any recognition. Now that one can view this hardline team of special operators in hindsight and that the veil of secrecy has been lifted, you can now understand the amazing efforts, impact and risks that were accomplished by the few brave soldiers of the SOG 1.

Works Cited

- Misirow, T. (Director). (2016, October 1). Warriors Behind the Lines [Video file]. Retrieved September 2, 2017, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bIY9oNlUD5A&t=1669s

- Smith, Jr., W. Thomas (2003). Encyclopedia of the Central Intelligence Agency. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 0-8160-4666-2.

- Popular Electronics, Volume 6, Issue 2–6. Ziff-Davis Publishing Co., Inc. 1974, p. 267. “There are three classifications into which the intelligence community officially divides clandestine broadcast stations. A black operation is one in which there is a major element of deception.”

- Djang, Chu, From Loss to Renewal: A Tale of Life Experience at Ninety, Authors Choice Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, p. 54. “(A black operation was) an operation in which the sources of propaganda were disguised or mispresented in one way or another so as not to be attributed to the people who really engineered it.”

- US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observations Group (1965). Annex A, Command History 1964. Saigon: MACVSOG.

- Shultz, Richard H. (1999). The Secret War Against Hanoi: Kennedy’s and Johnson’s use of spies, saboteurs, and covert warriors in North Vietnam. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-019454-5. OCLC 42061189

- “BAT 21”. Untold Stories. Vinh Biet Saigon. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Cummins, Joseph Éamon (November 1, 2004). The Greatest Search and Rescue Stories Ever Told: Twenty Gripping Tales of Heroism and Bravery. The Lyons Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-59228-483-2.

- Mack, Amy P. (July 26, 2010). “The Rescue of BAT-21”. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- Stoffey, Col. Robert E.; Holloway III, Admiral James L. (September 5, 2008). Fighting to Leave: The Final Years of America’s War in Vietnam, 1972-1973(first ed.). Zenith Press. p. 336. ISBN 0-7603-3310-6. Retrieved March 29,2011.

- Untold Stories. Vinh Biet Saigon. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Whitcomb, Darrel D. (1998). The Rescue of Bat 21. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. p. 196. ISBN 1-55750-946-8.

- Haseman, John B. (December 2008). “The Unsung Hero in the Amazing Rescue of Bat 21 Bravo”(PDF). Vietnam. HistoryNet.com: 45–51.

- “Michael Thornton Biography”. Academy of Achievement. Retrieved March 27, 2011

- Joint Chiefs of Staff (1970). Military Assistance Command Studies and Observations Group, Documentation Study (July 1970).

- http://www.roman-catholic-saints.com/roy-benavidez.html

- http://www.cmohs.org/recipient-detail/3229/benavidez-roy-p.php

- https://www.nytimes.com/2000/07/17/us/franklin-d-miller-55-hero-as-a-green-beret-in-vietnam.html

- https://army.togetherweserved.com/army/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=Person&ID=25629

- http://specialoperations.com/29014/worlds-first-combat-h-l-o-jump/

- MACV Command History 1971–72, Annex B, pp. 216, 300, & 383

- USMACV Strategic Technical Directorate Assistance Team – 158 Command History, 1 May 1972 – March 1973, p. 18

- Zimmerman, Dwight Jon; Gresham, John D. (October 14, 2008). Beyond Hell and Back: How America’s Special Operations Forces Became the World’s Greatest Fighting Unit. St. Martin’s Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-312-38467-8.

Good coverage. I was there, CCN FOB-4 DaNang 22 August 1968- 20 June 1969. Recon Team Cobra Went from SOG to Project Delta B-52 till 26 October 1969 Delta-Recon. Finest men I will EVER know!

Thank you MSG Pardee for your service and for reading my blog! I couldn’t imagine what you went through during your time in the service. Many people owe so much to you that they will never even know about. I’m glad you got something out of my post!

Also if there is anything else you’d like to add to my post, I would welcome and be honored by your comments. Just let me know and I can arrange it.

Is there any reason this is copied nearly word for word from the “Warriors Behind the Lines” youtube video? I know you’ve referenced it, but a lot of this is copied nearly word for word.

Milo. Thank you for reading my blog! It is true that I got much of my information from the YouTube video that I referenced, as well as several other places that were also referenced. However, much of my writing I put in my own words. You have a right to that opinion but as the writer, I know that my words are not “copied word for word”.

Thank you for publishing these stories, my father is Ssgt. Richard Woody, he was a Green Beret and a member of SOG, and more information about his service would be appreciated.

John. Thank you for reading my blog post! The research I put into this was very exciting and educational. Although I haven’t heard of your father, I appreciate his service. Many veterans who returned from the Vietnam War didn’t share their stories for many years…some not at all. Is your father still around?

Thank You for your Remarkable Courage and Service to this Country. I would like to buy you a beer or 3.

Salute

Kenny

U.S.Army (Ret)

Thanks for reading my post Kenny! I am amazed at the service of every one of our military members! Thank you for your service as well!

YOU DUdES, ARE TOP – NOTCH ALL THE WAY……